Friday, January 29, 2021

Shakespeare Apocrypha - Edmund Ironside

Thursday, January 28, 2021

Shakespeare Apocrypha - Fair Em, The Miller's Daughter of Manchester

Another day, another play. This one was really good. It had a certain charm. It also had an odd anachronistic feel to it. Which I quite liked.

There were two loosely overlapping plot strands. One focusing on Fair Em, and the various suitors attempting to woo her. The other concerning the love life of William the Conqueror. Imagine that. Quite a contrast.

The parts concerning Em set in Manchester felt very Elizabethan. Her father, the Miller, going by the name Sir Thomas Goddard. Though now, thanks to the yoke of the Norman Conquest just a lowly miller without the title. Likewise, when King William heads to Denmark in disguise he goes by the name Sir Robert of Windsor. So these more contemporary sounding names didn't quite sit right with 11th century Danes and Normans.

Consequently it felt slightly absurd.

Wednesday, January 27, 2021

Recently Read: The Merry Wives of Windsor

Monday, January 25, 2021

Shakespeare - Scenes of the Scenes

"[Monmouth] is best known for his chronicle The History of the Kings of Britain which was widely popular in its day [...] It was given historical credence well into the 16th century, but is now considered historically unreliable." - Wikipedia

However, both King Lear and Cymbeline fall under this general category too. So I may have to discount this idea.

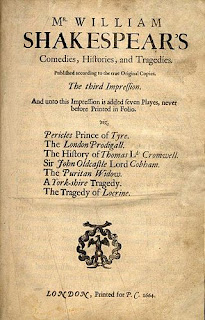

Finally, it perhaps would be useful to split the seven plays published as by Shakespeare or by W.S. into three general sub-categories. To delineate things a little more clearly.

English Plays:

The Yorkshire Tragedy, The London Prodigal, The Puritan

English History Plays:

Thomas Lord Cromwell, Sir John Oldcastle

Plays dealing with British history:

Locrine, The Birth of Merlin

Splitting things like this it would be easy to speculate that the last four plays may have been excluded simply because they're not good enough (or perhaps not tasteful enough). Thomas Lord Cromwell and Sir John Oldcastle have a similar feel to the history plays, but as the central figures aren't kings they lack that same gravitas. Also the fact that Oldcastle is a doppelganger for Falstaff muddies the pristineness further. A bit like when a different actor comes in to play a familiar character in a TV series. People don't really like it. We know it's just a TV show and that these aren't real people, but still, we like things to be consistent.

"That's not the right person!! They've ruined it!"

So I imagine having a version of the much-loved Falstaff in the collection, but with a completely different name would be a little too imperfect for some people.

It's also worth mentioning that the Protestant/Catholic factor may have had an influence on the inclusion of these plays too.

As for Locrine and Merlin, they could easily fall in with the other tragedies and comedies. However, it may be that they were simply too poor and unpalatable. It's a while since I've read Locrine, but when I read Merlin last month it was quite whacky lol. Personally I loved it, but I can imagine the general silliness not sitting well with more serious people.

Lastly, the three 'English Plays' are perhaps the most out of keeping with anything in the established Shakespeare canon. Though it should be noted that I've yet to read The Merry Wives of Windsor. Which may fall closest to this tree. So I should do that as soon as possible, once I've sped through the last six apocrypha ones.

Having read an overview of The Merry Wives I suspect that its inclusion owes itself largely to Falstaff appearing in it. How could they leave him out. So I'll be very interested to read it.

In fact, the opening paragraph on Wikipedia contains this line;

"The play is one of Shakespeare's lesser-regarded works among literary critics."

Sounds like my kind of play.

Perhaps it's a little too earthy and English for the critics though??

Then again ..perhaps it's just a bad play.

Saturday, January 23, 2021

Shakespeare Apocrypha - The Second Maiden's Tragedy

I've just finished The Second Maiden's Tragedy. (Yes, I'm flying through them now.)

This play's authorship is contested, but the general consensus seems to be that it's the work of Thomas Middleton. It's part of the Shakespeare apocrypha as it was loosely attributed to Shakespeare in the 17th century. By virtue of the fact that his name was scribbled upon the manuscript by someone (the play was never printed). However, two other names (Thomas Goffe and George Chapman) also had the same honour. So such scribblings are likely estimated guesses or wishful thinking on the part of the various scribblers.

A tyrannical king, simply named Tyrant in the play, tries to woo the lady of the former king he's usurped.

"He's lost the kingdom, but his mind's restor'd ;Which is the larger empire ? pr’ythee tell meDominions have their limits, the whole earthIs but a prisoner, nor the sea, her jailor,That with a silver hoop locks in her body ;They're fellow prisoners, though the sea looks bigger,Because it is in office and pride swells him ;But the unbounded kingdom of the mindIs as unlimitable as heav'n , that glorious court of spirits."

Tuesday, January 19, 2021

Shakespeare Apocrypha - Edward III

This should be a super short one. I've just finished reading Edward III. One of the Shakespeare apocrypha plays, but now generally considered to be part of the Shakespeare canon proper.

I don't have a great deal to add, other than to just tick it off my list. It was a pretty standard history play. As ever some of the poetic wordiness was impressive. With some nice flourishes and observations. In fact, like many of these plays it started slowly and a little laboured, then picked up apace. Almost like the writer needed time to get into the flow of things. After which the verses start pouring out.

As with the other plays it felt and read like a Shakespeare.

Sadly there wasn't a great deal of comedy or bawdiness, so it was a little plain for my tastes. Though I did enjoy the anti-French and anti-Scottish sentiment 😈

Definitely worth reading, but certainly not a favourite.

Monday, January 4, 2021

Shakespeare Apocrypha - The Two Noble Kinsmen

Wooer. Alas, I have no voice Sir, to confirme her that way.Doctor. That's all one, if yee make a noyse,If she intreate againe, doe any thing,Lye with her if she aske you.Iaylor. Hoa there Doctor.Doctor. Yes in the waie of cure.Iaylor. But first by your leaveI'th way of honestie.Doctor. That's but a nicenesse,Nev'r cast your child away for honestie;Cure her first this way, then if shee will be honest,She has the path before her.

Emilia. [...] That the true love tweene Mayde, and mayde, may beMore then in sex individuall.Hippolyta. Y'are ont of breathAnd this high speeded-pace, is but to sayThat you shall never (like the Maide Flavina)Love any that's calld Man.

I find it hard to believe that any intelligent man of learning, living in England at that time, could have chosen to be Catholic. Protestant possibly, atheist maybe, agnostic more likely, but a practising Catholic - a bit of a stretch.